Should we be worried by ever more CCTV cameras?

It is all quiet on a mid-morning weekday at the CCTV monitoring centre of Southwark Council, in London, when I pay a visit.

Dozens of monitors display largely mundane activities – people cycling in a park, waiting for buses, coming in and out of shops.

The manager here is Sarah Pope, and there is no doubt that she is fiercely proud of her job. What gives her a real sense of satisfaction is “getting the first glimpse of a suspect… which can then guide the police investigation in the right direction,” she says.

Southwark shows how CCTV cameras – that fully adhere to the UK code of conduct – are used to help catch criminals and keep people safe. However, such surveillance systems do have their critics around the world – people who complain about a loss of privacy and an infringement of civil liberties.

Manufacturing of CCTV cameras and facial recognition technologies is a booming industry, feeding a seemingly insatiable appetite. In the UK alone, there is one CCTV camera for every 11 people.

All countries with a population of at least 250,000 are using some form of AI surveillance systems to monitor their citizens, says Steven Feldstein from the US think tank Carnegie. And it is China that dominates this market – accounting for 45% of the sector’s global revenue.

Chinese firms like Hikvision, Megvii or Dahua might not be household names, but their products may well be installed on a street near you.

“Some autocratic governments – for example, China, Russia, Saudi Arabia – are exploiting AI technology for mass surveillance purposes,” Mr Feldstein writes in a paper for Carnegie.

“Other governments with dismal human rights records are exploiting AI surveillance in more limited ways to reinforce repression. Yet all political contexts run the risk of unlawfully exploiting AI surveillance technology to obtain certain political objectives,”

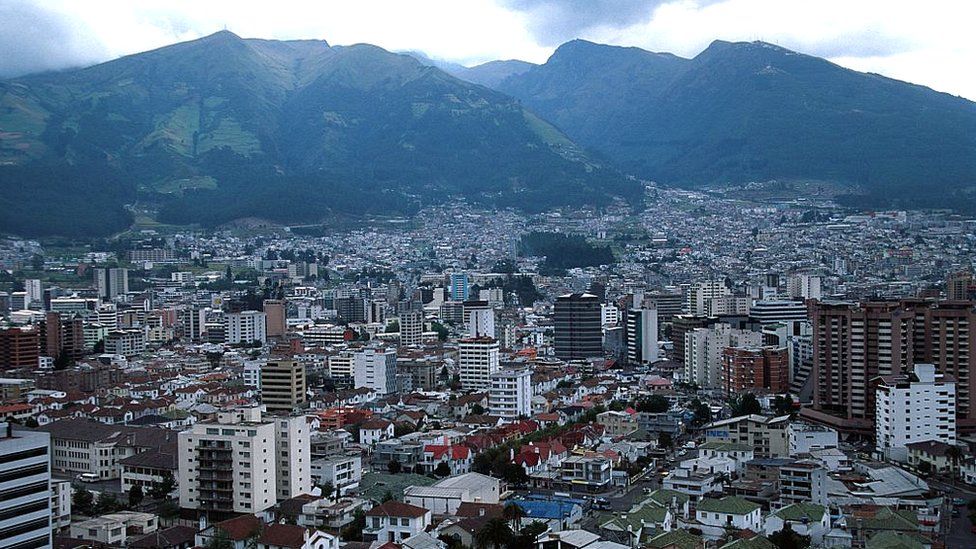

Ecuador has ordered a nationwide surveillance system from China

Ecuador has ordered a nationwide surveillance system from China

One place that offers an interesting insight into how China has rapidly become a surveillance superpower is Ecuador. The South American country bought an entire national video surveillance system from China, including 4,300 cameras.

“Of course, a country like Ecuador wouldn’t necessarily have the money to pay for a system like this,” says journalist Melissa Chan, who reported from Ecuador, and specialises in China’s international influence. She used to report from China, but was kicked out of the country several years ago without an explanation.

“The Chinese came with a Chinese bank ready to give them a loan. That really helps pave the way. My understanding is that Ecuador had promised oil against those loans if they couldn’t pay them back.” She says a military attaché in the Chinese embassy in Quito was involved.

One way of looking at the issue is not simply to focus on the surveillance technology, but “the export of authoritarianism”, she says, adding that “some would argue that the Chinese are far less discriminating in terms of which governments they’re willing to work with”.

For the US, it is not the exports so much that are a concern, but how this technology is used on Chinese soil. In October, the US blacklisted a group of Chinese AI firms on the grounds of alleged human rights abuses against the Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang region in the north-west of the country.

China’s largest CCTV manufacturer Hikvision was one of 28 firms added to the US commerce department’s Entity List, restricting its ability to do business with US companies. So, how will this affect the firm’s business?

Hikvision says that earlier this year it retained human rights expert and former US ambassador Pierre-Richard Prosper to advise it on human rights compliance.

The firms adds that “punishing Hikvision, despite these engagements, will deter global companies from communicating with the US government, hurt Hikvision’s US businesses partners, and negatively impact the US economy”.

Olivia Zhang, the US correspondent for Chinese business and finance media firm Caixin, believes there could be some short-term problems for some on the list, because the main microchip they used was from US IT firm Nvidia, “which would be hard to replace”.

She says that “so far, no-one from the Congress or the US executive branch has offered any hard evidence” for the blacklisting. She adds that Chinese manufacturers believe the human rights justification is just an excuse, “the real intention is just to crack down on China’s leading tech firms”.

While the surveillance producers in China bat away criticisms of their involvement in the persecution of minorities at home, their revenues rose 13% last year.

The growth this represents in the use of technologies like facial recognition poses a big challenge, even for developed democracies. Making sure it is used lawfully in the UK is the job of Tony Porter, the surveillance camera commissioner for England and Wales.

On a practical level he has many concerns about its use, in particular because his main goal is to generate widespread public support for it.

“This technology operates against a watch list,” he says, “so if the face recognition identifies somebody from a watch list, then a match is made, there’s an intervention.”

He questions who goes on the watch list, and who controls it. “If it is the private sector operating the technology, who owns that – is it the police or the private sector? There are too many blurred lines.”

Melissa Chan argues that there is some justification for these concerns, especially with regard to Chinese-made systems. In China, she says that legally “the government and officials have a final say. If they really want to access information, that information has to be handed over by private companies.”

It is clear that China has really made this industry one of its strategic priorities, and has put its state might behind its development and promotion.

At Carnegie, Steven Feldstein believes there are a couple of reasons why AI and surveillance is so important to Beijing. Some are connected to “deep rooted insecurity” over the longevity and sustainability of the Chinese Communist Party.

“One way to try to ensure continued political survival is to look to technology to enact repressive policies, and suppress the population from expressing things that would challenge the Chinese state,” he says.

Yet in a wider context, Beijing and many other countries believe AI will be the key to military superiority, he says. For China, “investing in AI is a way to ensure and maintain its dominance and power in the future” .